Project 8821

Inspired by Quinn Dunki’s Veronica project to explore the 6502, I’ve decided to build a 6809E-based hardware platform for old Williams coin-op videogames, such as Defender, Robotron, Stargate, Bubbles, Sinistar, and Joust.

Ah, Joust. How many first-period high school classes did I miss because of it in 1982? As a result of a software bug involving lava trolls and pterodactyls, I got hours and hours of experience from a single quarter that should have lasted maybe three minutes in a normal game. Williams quickly fixed the bug with a new ROM revision, but my skills were established. I was the first kid in my county to “turn over” Joust from a score of ten million back to zero again.

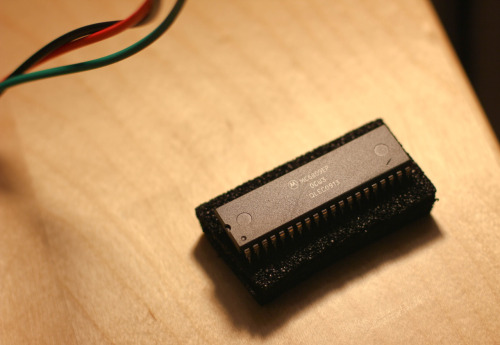

Twenty years later, I found a rare cocktail version of the game for sale, and for $800 it was mine. But it didn’t last long; like so many Williams games of its era, its DRAM died and its video burned out. Today it gathers dust in storage. The easy path to playing again (well, other than selling it and downloading MAME) would be to replace the bad components. But that’s no fun. It’d be just a small matter of online shopping. What if instead I started with this:

and built it into a working Joust system? And as long as I was at it, why not get the other Williams games that ran on near-identical hardware to run, too? It’d be a chance for a software guy like me to get a layer or two lower in the stack, and I’d end up with something presumably more reliable, cooler, and cheaper to run than the early-1980s hardware that John Newcomer and Eugene Jarvis had to work with. Yeah, that’s more like it!

I hereby commence Project 8821 (6809 + 2012… hey, you come up with a better name). Here are the ground rules, subject to change on personal whim:

- The software portion of the games must remain unchanged. I can use any hardware I want, but the exact bits living in the original ROMs must work on whatever I build. Exceptions: I’ll fix Robotron’s shot-in-the-corner bug using Sean Riddle’s patch, and I might have to change 3 bits in Defender to work with later hardware, which is OK because I actually never liked that game.

- I’ll start with original hardware, such as the real 6809E that I picked up today from Jameco, but where reasonable for cost, availability, pedagogical, elegance, or sanity reasons, I’ll substitute newer technology, such as SRAM to replace the 24 individual 4116 chips.

- I have no desire to keep replacing burned-out CRTs, so I’ll change the video to use VGA, possibly using the methodology described by the fine folks over at Lucid Science.

- This isn’t a reverse-engineering project where I’m pretending to work in a clean room. I fully plan to take advantage of all information available, including anything I get can out of existing similar projects. (Unfortunately, jrok seems to have dropped off the face of the earth, so I’m not sure how much help his work will be.)

- No processor emulation unless I write the emulator myself. That rules out MAME on a Raspberry Pi, which would otherwise be a very sensible approach to replacement hardware in the original cabinet, if I wanted to complete the project in an afternoon and didn’t care about the educational aspects.

Before you think I’ve gone off the retro deep end, understand that the ultimate goal of this project, once I have a hardware copy running, is to move as much of it as possible to software. That means FPGA, which in my mind counts as hardware and doesn’t break the no-emulation rule. The current Papilio One platform isn’t quite capable enough for this project because of BRAM limits, but the forthcoming Papilio Plus, with a separate SRAM chip, ought to fit everything quite comfortably. When you can buy a generic FPGA development board and download the entirety of this project (minus ROMs for legal reasons) from GitHub, the project will be complete.

This is a big job that’ll probably take a year. But I think it’ll be fun, and I hope you’ll enjoy following along.